Advertisement

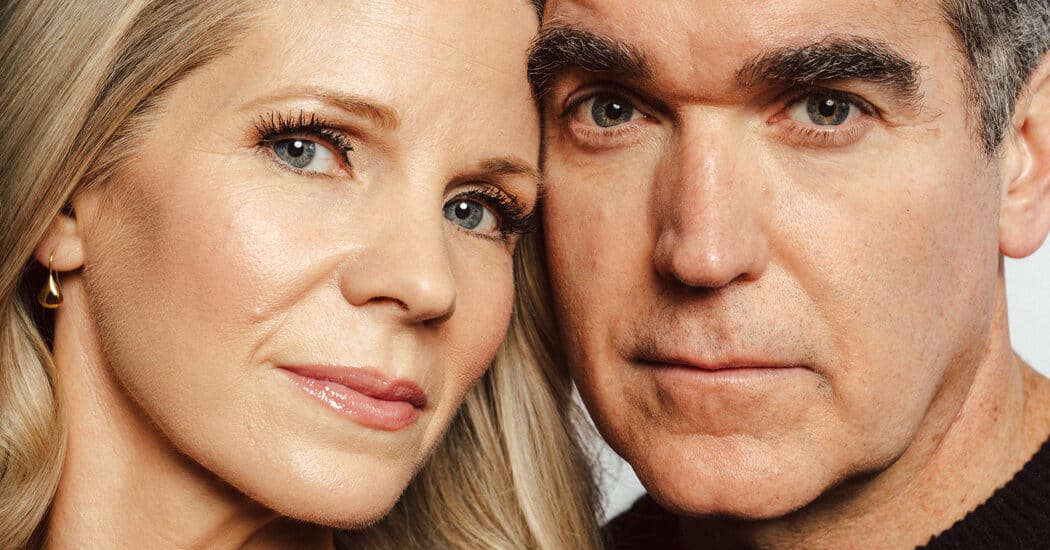

Kelli O’Hara and Brain d’Arcy James didn’t let the door close on their new Broadway musical about a couple undone by addiction.

As origin stories go, the transformation of “Days of Wine and Roses” from a movie into a musical is a straight shot, with a twist. Kelli O’Hara and Adam Guettel had the inkling more than 20 years ago, when she was a Broadway ingénue, working on what became her breakthrough Tony-nominated role in “Light in the Piazza.” Guettel had written the music and lyrics for that musical, which went on to earn him a Tony Award for best score. They talked through their coordinating vision for evolving “Wine and Roses,” the midcentury classic of a romance ruined by addiction. “I think I used the words ‘a weird dark opera,’” O’Hara recalled.

She already had a co-star in mind: Brian d’Arcy James, debonair and wry, like Jack Lemmon was in the 1962 movie, opposite the O’Hara look-alike Lee Remick. The film memorably traced the stuttery arc of alcoholism and recovery, a trajectory now familiar — onscreen and off — but rarely put to song.

Guettel was not only game to try, he eventually brought in the playwright Craig Lucas, the Tony-nominated book writer for “Light in the Piazza.” Both had, separately, been facing their own addictions, in ways that informed, and sometimes overlapped with, the show’s development.

The twist, then, is that, two decades on, the musical about a whiskey-soaked couple has actually arrived on Broadway — it opens on Sunday — starring O’Hara and James, now in the prime of their careers, with gorgeously matched vocals. The production takes pains to show the love that propels their characters’ relationship — however misguided it turns out to be.

“The show sort of has ‘underdog’ written all over it,” Guettel said in a recent phone interview. Friends and associates wondered why he was pursuing it: the material was tragic, the characters weren’t likable, they said. “My response was, ‘Well, Sweeney Todd wasn’t exactly someone you had over for Sunday brunch.’”

“It’s an unlikely project, and everyone stuck with it,” he added. “The thing works, I think, in large part because of that loyalty.”

Image

“Days of Wine and Roses” started as a teleplay in 1958, by the writer JP Miller, who was interested in dramatizing Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. It follows Joe, a hard-drinking PR executive, and Kirsten, an ambitious secretary and teetotaler; when they pair up, she starts in on the bottle. Marriage and a daughter follow; they’re functional alcoholics until they’re not. One finds sobriety through A.A., and the other sinks further away.

It is carried almost entirely by O’Hara and James, who met on the short-lived 2002 musical “Sweet Smell of Success” and, for the last decade or so, have been meeting regularly as they developed “Days of Wine and Roses.” Their chemistry is palpable from the stage, and in a joint phone interview they compared the exhilaration of working on the show to skydiving. “It is a partnership like no other that I’ve had in the creation of something onstage,” James said.

That didn’t make it easy, said Lucas, who is also known for his plays, like “Prelude to a Kiss” and “Reckless.”

“These are artists who look at every little turn in a phrase and go, ‘Why? Why that? Why not this? Do we need that?’” he said. “I so admire that.”

In her New York Times review of its premiere last year, at Off Broadway’s Atlantic Theater Company, Laura Collins-Hughes called it “a jazzy, aching musical” with an “awfully glamorous” central pair. And O’Hara, who then as now sings 14 of the 18 numbers in the show, was, she wrote, “in exquisite voice.”

During that run and in previews on Broadway, O’Hara said she quickly understood how viscerally the narrative connected with audiences. One theatergoer came up to her after a show, “with a full drink in her hand,” she said, “crying and hugging me and saying, ‘you know, I’m a mother and I worry about my drinking.’ And she was quite past sobriety at that point.”

Another woman walked by and thanked her, quietly adding, “‘23 years’ — meaning 23 years sober,” O’Hara said.

Few people’s lives, she noted, have not been touched by addiction. “I lost a couple of friends to this over the pandemic, and I think many people got sober over the pandemic,” she said. Even though there’s more understanding of its pervasiveness than “in the time of Kirsten and Joe, it’s not changing, it’s not ending, and it won’t.”

Life unraveling is often fodder for musicalization; inebriation just adds another layer, Michael Greif, the show’s director, said. “Craig and Adam were on to, very early, the kind of emotional expansiveness that the drunkenness could provide,” he said. With cocktails clinking, the characters have a sense of abandon — good and bad. “First, it takes them to dizzying heights” — the staging literally elevates them — “and then ultimately brings them to horrific, horrific loneliness,” Greif said.

“You always have that moment with, ‘Why? Why do we now move into song?’” he added. “And in this piece there’s a very clear lubrication, a very open doorway into that kind of expression.”

For everyone involved, it was important to present alcoholism not as we view it now, as an illness, but as it was seen several generations ago, as a test of willpower. “It’s not my job to necessarily give you a flowchart of what the science of addiction is,” James said. “It’s really to honor the connection of two human beings who are in love and have a problem.” Contextualizing Joe and Kirsten in their era, “the vocabulary is limited. They’re unequipped really to talk about it, figure it out, or try to correct it.”

That’s where the songs come in. Lyrically, they leap from effervescence to despair, sometimes, cunningly, in one number. Into previews, Guettel was still fine-tuning some music — “to truly interpret the kinds of sounds that were happening in the late ’50s, early ’60s in New York for a certain echelon of people who thought jazz was” the be-all, he said. “We want them to have associations with Eric Dolphy or very early Bill Evans or Thelonious Monk.” In one song, “Are You Blue,” O’Hara improvises with the band, her otherworldly soprano a contrast to the splintery score.

Image

Though there are other characters — an A.A. sponsor; Kirsten’s stern father — Guettel chose to have only Kirsten, Joe and, occasionally, their daughter, sing. “For me, it was the most important piece that I’ve ever done in that sense that I could really sculpt this for these two great artists,” Guettel said.

The creators also resisted adding any contemporary gloss to the relationships. Kirsten chafes, but only very little, at becoming a full-time mother instead of a working one. Joe is sometimes boorish and clueless about her needs and priorities. Their child (played by Tabitha Lawing) largely raises herself, as they drown their despair in clinking glasses.

“I feel very strongly that the social and cultural mores of that era are almost a character in the show,” Guettel said.

For Lucas, the milieu was familiar. “There was a whole completely different ethos around drinking in the ’50s,” he said, “where everyone my parents knew drank, drank, drank, drank; you were thought to be a pill if you didn’t. And I remember them talking about recovery and looking so down on people who did that.”

His parents “were loving. They adored me. They gave me everything,” he added. “These were people who sacrificed for me, and I adored them, but they drank themselves to death.”

He has been sober for 19 years, he said, tearing up in a video interview as he talked about it. “When you’re in the grip of it, there’s a little voice that says, ‘I can control this, right?,’” he said. “Alcoholism is the disease that tells you, you don’t have a disease.”

That tension is what he found fascinating about the original work. Miller, the teleplay writer, “designed this kind of Swiss watch that just kept tightening up on these people,” he said. They didn’t have the benefit of knowing — as A.A. teaches — that you need a network of support. “The great big secret, which many of us were never taught, is that life is only meaningful to the degree that you were of service to others,” he said. “I didn’t know that.”

For Guettel, sobriety came around and alongside the show’s development, in ways that he was reluctant to delve into, though it did include A.A., he said. (He also has a familial history of addiction; his grandfather, the composer Richard Rodgers, was the sort of alcoholic who hid liquor in the toilet tank.) “I don’t write about winners; I write about people,” Guettel said. “And I am certainly not a winner. I’m the person — I’ve had my ups and downs, but things are very stable now, and have been for quite a long time.”

“I’m very happy to have had a way to process that through writing this piece,” he added. He was mindful that it not turn preachy — it’s not “a cautionary tale, a morality play, nothing like that,” he said. “They’re all heroes, even though this is a tragedy.”

For the actors, one of biggest hurdles was also, in this production, the most basic: acting drunk. It’s one of the hardest things for a performer to do, the cast and creative team said. (People who are inebriated, after all, are mostly trying to appear sober.) There’s a fear, James said, that the audience won’t believe it because they “see the mechanics of a person trying to act like they’re drunk.”

Overcoming that started with physical craft, imagining “that your body is not in control,” he said. “There is great joy, in trying to kind of unleash oneself — it’s dangerous, and it’s not contained. So as an actor, that’s a lot of fun to do.”

“Fun” is not a word normally associated with “Days of Wine and Roses,” which so bleakly shows the splintering of a family. But O’Hara, too, had to find moments of positivity in even in the steepest spiral. “We go on because there are moments of hope,” she said. “There are moments of completion and success, in life and in motherhood and marriage, and in this story that we tell.

“I come off the stage feeling emotional, but elated and proud and breathless — literally breathless — from the freedom to be given a challenge like this and to be trusted with it,” O’Hara added.

It didn’t start out as a passion project. But now, between the years in development, the exhilaration of the performance and the audience connection, “I’ve never been so passionate about anything in my life,” she said.

Melena Ryzik is a roving culture reporter and was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for public service for reporting on workplace sexual harassment. She covered Oscar season for five years, and has also been a national correspondent in San Francisco and the mid-Atlantic states. More about Melena Ryzik

Advertisement